Mainstream music and live concerts have become such a spectacle of scrutinizing vocal ability and production quality that performance seems to have become obsolete. People don’t care about having a good time at concerts anymore; they want content–moments engineered for clips, viral discourse, and side-by-side comparisons with studio recordings. A live show is no longer allowed to be fleeting or imperfect. Instead, it’s expected to function like a polished product, endlessly replayable and judged long after the lights come up.

And when an artist doesn’t sound perfect within that content, it’s treated as failure rather than honesty. Cracked notes, breathlessness, and raw emotion are framed as evidence that the artist “can’t sing.” Audiences have quite literally become a panel of critics, phones raised, standing around and waiting for something to happen on stage that they can validate or condemn.

Live music has always had its flaws–the unpredictability, the mistakes, the way a song could make or break the show depending on how the night is going. There’s a level of raw emotion that only comes when you’re face to face with people wanting to hear your music. Live music is supposed to be loud, sweaty, and unrepeatable–something you had to be there for. And yet, these flaws have been minimized in recent years, and concerts have started to resemble rehearsed simulations of themselves, safe enough to satisfy the algorithm but distant enough to leave people untouched.

When the conversation about how Taking Back Sunday sucks nowadays comes up, it almost always circulates back to the same tired talking points: Adam Lazzarra’s voice isn’t what it used to be, they miss notes, the songs don’t hit the same way they did on the record twenty years ago. People complain that the tempos are off, that the band sounds “unprofessional” or “washed up,” and their delivery is sloppy. Someone always posts a shaky phone video as evidence, with a strained chorus on a particularly off night and treats that like empirical evidence.

There’s also the nostalgia argument, that Taking Back Sunday has lost whatever magic they had in the early 2000s, that they should either sound exactly like Tell All Your Friends forever or stop playing altogether, as if the only acceptable version of a band is one that existed when fans were younger, angrier, and projecting their own feelings onto them. To some, their growth is framed as betrayal, and anything short of perfect replication is proof they’ve “fallen off.”

And to this, I say, who gives a fuck?

Taking Back Sunday concerts have never been about technical perfection. They’ve been about urgency, about shouting along with your friends until your throat burned, about a voice cracking because the emotion couldn’t wait to be delivered cleanly. Adam Lazzara didn’t become iconic because he sang like some conservatory-trained vocalist. He became iconic because he sounded like someone unraveling in real time. That was the point. That is the point.

Saying they “don’t sound like they used to” ignores the most obvious truth: they aren’t who they used to be, and neither are the people who go out of their way to sell out a once-a-year experience at a dinky little concert venue in the middle of New Jersey. If Taking Back Sunday stayed frozen in the same shape they were in the 2000s, that would be dishonest, and expecting a 44-year-old man to scream the way he did at 22 is absurd.

If you’re at a Taking Back Sunday show counting pitch errors instead of screaming the words back at the stage, you’re doing concerts wrong. Fortunately, their annual holiday shows aren’t designed for quiet evaluation.

For the 11th year in a row, Taking Back Sunday returned to their annual holiday shows at Mulcahy’s Pub on Long Island and Starland Ballroom in Sayreville, New Jersey. The tradition alone sets a certain expectation: rowdy, emotional, and familiar in the way only a long-running hometown set can be.

The first opener on Friday, December 12th, was Kayleigh Goldsworthy, an artist I wasn’t familiar with until she mentioned she’d written a song for John Nolan’s Music For Everyone Vol. 2, which she then performed in full. Her set was stripped down and intimate, hovering somewhere between country and folk and featuring just herself and an acoustic guitar. Her performance was undeniably beautiful, although it felt slightly out of place against the chaotic lineup coming up. The crowd seemed unsure of how to respond, but they listened attentively and gave Kayleigh the respect she deserved.

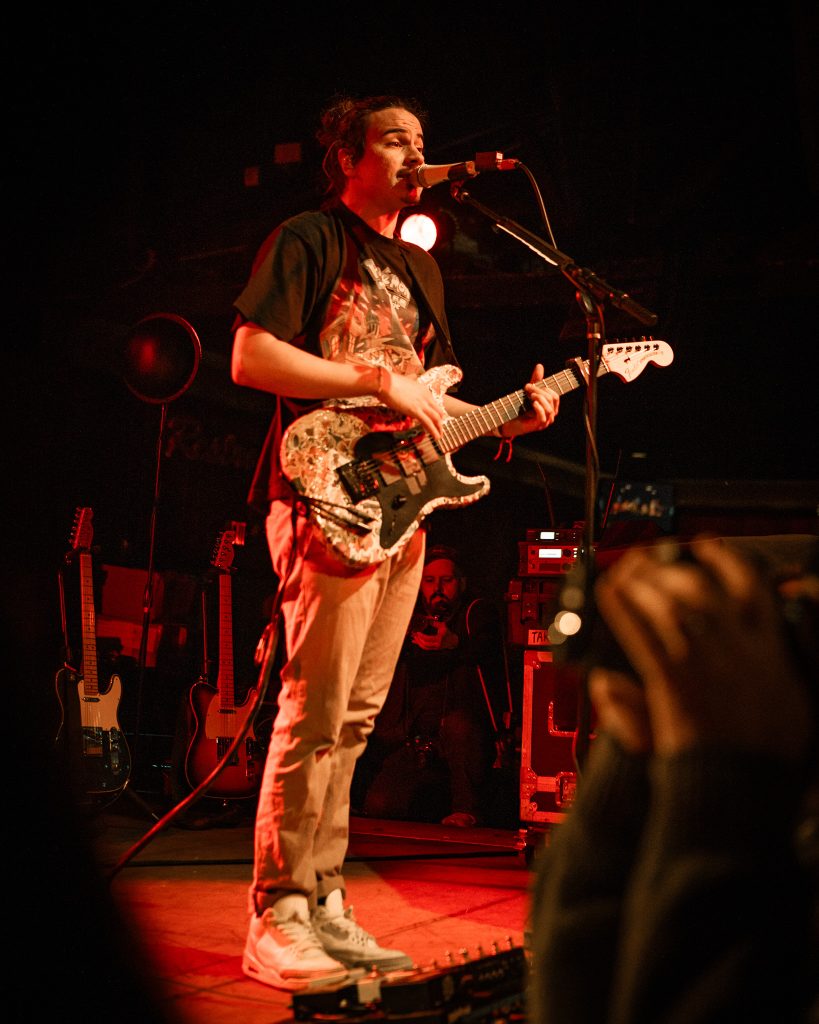

Origami Angel followed, and the shift in energy was immediate. I had assumed they were a full band, but when they took the stage, I realized they were just two people: Pat Doherty on drums and Ryland Heagy on everything else. Despite their minimal setup, their sound echoed throughout Starland Ballroom. It was obvious that a significant portion of the crowd were fans of the headliner and Origami Angel, as people at the barricade sang along word for word, feeding off the band’s momentum with genuine excitement and intensity. My only critique about Origami Angel was the fact that they didn’t sing “Thank You, New Jersey.” As a lifelong resident of this wonderful state, not hearing “Thank You, New Jersey” in New Jersey was insulting.

By the time Origami Angel finished their set, the room felt awake. The polite, uncertain stillness that hovered during the first opener had been replaced with movement: heads nodding, bodies pushing closer to the stage, voices warming up for what everyone was ultimately there for.

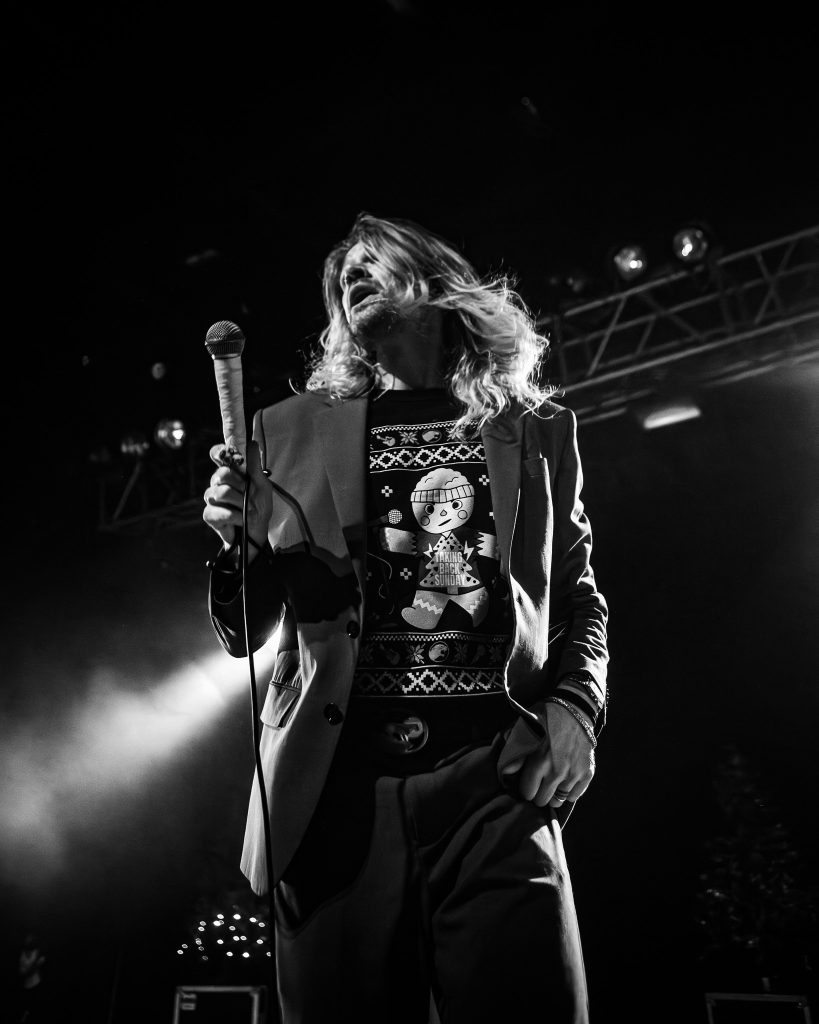

The Taking Back Sunday set officially began with Andy Williams’ “It’s the Most Wonderful Time of the Year,” a kitschy, almost-ceremonial cue that signaled what everyone already knew was coming. The stage was arranged with intention, with the band positioned around the perimeter, leaving the center wide open for Adam Lazzara to do his thing. They ran onstage wearing their iconic matching suits and jumped into “What’s It Like To Be a Ghost?”

The room exploded with energy, and when I turned around to grab a crowd shot, all I saw was a mass of bodies pressed shoulder to shoulder, jumping, shoving, and screaming every word back at the stage like muscle memory. That moment, that loud, chaotic, and impossible to cleanly document moment, was the entire counterargument to every bad-faith clip posted online to prove Taking Back Sunday “doesn’t sound good anymore.”

John Nolan was absent due to a family emergency, but that never became a liability for the band. Fred Mascherino stepped in seamlessly, delivering with the kind of ease that highlights how deeply ingrained the band’s chemistry is, even when the lineup shifts. Lazzara, meanwhile, performed with a natural confidence that teetered on the edge of sermon and spectacle. He didn’t chase the crowd’s approval; rather, he knew that it was already there. The energy in the room hinged entirely on his willingness to let go, to move like someone experiencing the music alongside everyone else instead of presenting it for evaluation.

And that’s where everything circles back. That’s exactly what modern concert discourse refuses to account for: that the value of a live show isn’t found in control, but in exchange. In places like Starland Ballroom, flaws are proof that something real is happening. What happens at these holiday shows only works because it’s communal.

Taking Back Sunday rejects the idea that a concert owes you proof of value, and people don’t attend their shows to observe whether or not they “still have it.” They attend to remember that music doesn’t need to be perfect to be meaningful, and that sometimes, the most honest performances are the ones that happen right in front of you.

Follow TAKING BACK SUNDAY | WEBSITE | INSTAGRAM | FACEBOOK | SPOTIFY | APPLE MUSIC

Leave a Reply